This is the text of a speech I delivered on September 22, 2016

Twenty two years ago, when I was almost thirty six, I woke up one morning and said “Lynn, I’m sick.”. I had been in bed for weeks. I’d lost my appetite. We made an appointment with the psychiatric department at Kaiser Redwood City and by the end of the following week I was on Prozac.

Prozac was amazing stuff: I was cured the next day. My psychiatrist was surprised but because i had never told him about my other symptoms — the irritability, the paranoia, the rapid speech, that time in college when i had gone up to San Francisco with my girlfriend and come back with my girlfriend and they were two different people — he let things be. In time, our insurance changed, so I came under the care of a nice gentleman in Menlo Park who also had no clue about my other symptoms so he made no changes. Then we moved down here and I found a new psychiatrist who also made no changes because I never told her about my other symptoms either.

Then one day the Prozac stopped working, so she changed me over to Effexor. I found myself in a burning darkness. Two things happened. First, an editor was taking forever to get back to me on a story. Second, I overheard Lynn saying something about me to her sister. My irritability merged with my despair. I went for a walk in Whiting Ranch, called a friend — who found my anxiety funny for some reason. So I texted my last will and testament to Lynn, making special note to leave some possessions of my father to my nephew and asking her to be sure to be sure to get my poetry published after my death. Then I sat down on a sycamore log, studied my veins, and prepared to bread my glasses.

My cell phone rang. It was my psychiatrist. “Are you all right?”.

“No,” I whimpered. She told me to go down to South Coast Medical Center. Lynn picked me up and drove me to Laguna Beach

After spending several hours in the emergency room getting my chest x-rayed because I was wheezing, they took me down to the behavioral unit where I left Lynn at the door. They took away my shoelaces and my glasses, then showed me my room.

I came out after an hour. “I am diabetic,” I yelled. “I need my blood sugar medicine!” I can only imagine what was going through their minds — “this guy was brought here because he was preparing to commit suicide and now he wants the medicine her takes to keep himself alive” — but I am sure they took careful notes.

The next day when i went to group i was the happiest person there. Everyone was miserable except for me who was laughing at the fact that he had attempted suicide and lived to tell about it.

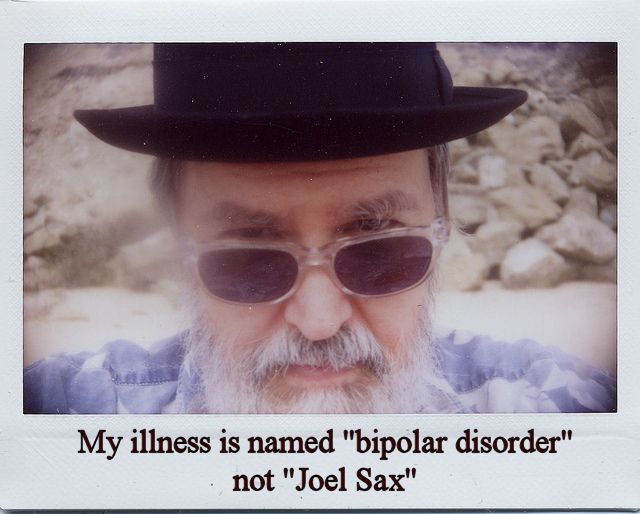

After group, I waited around until I was called into a consulting room. A psychiatrist joined me there. He took a few minutes to read over the notes the ER doctor and the nurses had made. Then he looked at me and asked in a very gentle voice “Had anyone ever told you that you were bipolar?”

And that is when my recovery began.