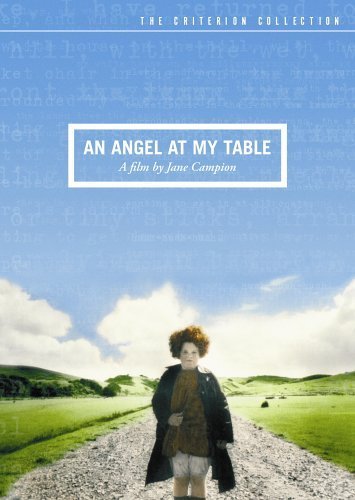

Janet Frame endured eight years as a mental patient before she went on to become the poet laureate of New Zealand. She was misdiagnosed. While she was incarcerated she underwent electro-convulsive therapy without anesthesia and was lined up for a lobotomy until her doctor learned that she had won a prestigious literary prize and took her off the list. This movie is the story of three periods in her life. Her time in a mental hospital is the second.

I would guess that social anxiety and, perhaps, depression were the demons that afflicted Frame. She would hide in corners. She failed at her work as a teacher. When two of her sisters died, she crashed into a frozen despair.

If Angel at My Table is accurate, Frame was most certainly not schizophrenic. An early scene in the second part of the film shows her riding to the hospital in a car with two women who are severely impaired by their illnesses. She stands out as unafflicted by whatever is troubling her fellow passengers. Things were done to her while she was in the hospital just because they were the latest treatment. Her mother desperately signed the papers for the lobotomy: if Frame had been trapped in a mindless system, we would have lost a great author. Fortunately, a doctor noticed in time and helped her win her release.

In the third part, she checks herself into a British mental hospital after the end of a happy love affair and finds that she had been misdiagnosed. She is not schizophrenic. All these years of dreading the melting of her mind had been for naught. Her new freedom from worry allowed her to go on and become the literary star that she is today.

Misdiagnosis does happen. I was talking to a psychiatrist recently who voiced his concern about a rise in faulty diagnoses of bipolar disorder. Patients present to their psychiatrists with depression and anxiety. The doctor quickly reviews their case and writes up a prescription for a mood stabilizer. This doctor has found himself correcting the work of ten minute marvels repeatedly lately, usually changing the diagnosis to depression and anxiety as the symptoms indicate.

The film succeeds because it is not an anti-psychiatry bash, but the tale of a woman whose doctors made a mistake. If the system let her down, it was also the system that saved her, saw her for what she really was, and sent her on her way to success. Though the film is not about bipolar disorder, I find it a worthy viewing for family members who want to know what it is like for the patient. The conditions of the fifties — the water cures, the strait jackets, the padded rooms, the unanesthesized ECt, and the lobotomies — may be gone, but the themes of dignity ring true for many of us today. How many of us have wondered if we are really mentally ill? Many. And a few have been right.

Follow

Follow