*TRIGGER WARNING*

I must tell the truth here: I do not understand what Andreas Lubitz did. In my suicidal fugues, I thought of many ways that I might kill myself that involved others such as throwing myself in front of a truck or crashing my car into a tree or driving it off a cliff, but the idea of taking others with me — that wasn’t the self-annihilation that I planned. When I came close,I found a secluded place where someone would eventually find me. That was the maximum involvement of another that I planned. Though I thought capital punishment might work for me — and send a message to those who loved me — I did not want to assassinate others.

I must tell the truth here: I do not understand what Andreas Lubitz did. In my suicidal fugues, I thought of many ways that I might kill myself that involved others such as throwing myself in front of a truck or crashing my car into a tree or driving it off a cliff, but the idea of taking others with me — that wasn’t the self-annihilation that I planned. When I came close,I found a secluded place where someone would eventually find me. That was the maximum involvement of another that I planned. Though I thought capital punishment might work for me — and send a message to those who loved me — I did not want to assassinate others.

>Rumor has it that Lubitz was going through some catastrophic issues with his girlfriend. He knew that he was ill and he was seeking treatment for it. The day of the crash, his psychiatrist issued a sick leave note. Andreas did not use it, however, and his doctor could not call the airline to tell them that he was at risk. But Lubitz did not stop at ending his own life:

Andreas Lubitz was breathing, steady and calm, in the final moments of Germanwings Flight 9525. It was the only sound from within the cockpit that the voice recorder detected as Mr. Lubitz, the co-pilot, sent the plane into its descent.

The sounds coming from outside the cockpit door on Tuesday were something else altogether: knocking and pleading from the commanding pilot that he be let in, then violent pounding on the door and finally passengers’ screams moments before the plane, carrying 150 people, slammed into a mountainside in the French Alps.

In a different article, The New York Times reported that Lubitz concealed his illness from those closest to him:

Peter Rücker, a member of the flight club where Mr. Lubitz learned to fly, told Reuters television on Thursday that he knew the young man as a cheerful, careful pilot, and that he could not imagine him committing such an act.

Online, Mr. Lubitz appeared to be a keen runner, including at Lufthansa’s Frankfurt sports club, and had completed several half-marathons and other medium-distance races, including an annual New Year’s run in Montabaur in 2014.

A Facebook page with a few tidbits of his possible “likes” was visible Wednesday but had been removed by late morning on Thursday. It showed a photograph of a young man near the Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco, though there were no clues to when the image was taken or any other details….

Data from the plane’s transponder also suggested that the person at the controls had manually reset the autopilot to take the plane from 38,000 feet to 96 feet, the lowest possible setting, according to Flightradar24, a flight tracking service. The aircraft struck a mountainside at 6,000 feet.

Before Mr. Lubitz, 27, a German citizen, set the plane on its 10-minute descent about half an hour into the flight from Barcelona, Spain, to Düsseldorf, Germany, the cockpit voice recorder picked up only the usual pilot banter, “courteous” and “cheerful” exchanges, the prosecutor said.

Then the commanding pilot asked Mr. Lubitz to take over. A seat can be heard being pulled back and a door closing as the captain exits the cockpit.

Lufthansa, the parent company of Germanwings, takes the position that nothing could be done, that even the best system in the world cannot protect the public 100% from such disasters. And they are confident that they have a good one.

I am not a big fan of willy nilly violations of confidentiality. It seems to me, however, that there should have been a way for the doctor to tell the airline that Lubitz was a danger to self and others and see that he was grounded. There should be ways for the pilot to open the door from the outside of the cockpit or to place a toilet inside the cockpit so he doesn’t have to enter the passenger section of the plane. So many things can have been done differently, but I am afraid that this is not where the media, public opinion, and politics will take us. The Times’ restraint will almost certainly be accompanied by more shrill attacks on the mentally ill among us. Lubitz, I dread will become another hockey mask, another poster child who will be held up as a clarion call for denying the mentally ill their confidentiality. Laws stand before Congress that call for allowing “caregivers” to be informed of what goes on between psychiatrists and the most severe mentally ill. Will Andreas Lubitz’s crash take us another step? Who else will psychiatrists be forced to inform? How will confidentiality be broken after this incident? Who else will be able to enter the circle that HIPAA laws now defend? I shudder at the possibilities.

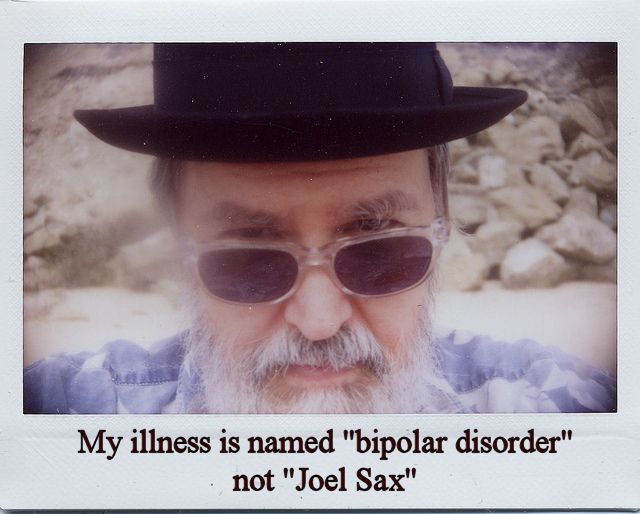

We must look, I think, at another major factor in this crash: stigma. Some out there think that stigma like racism no longer exists or impacts on lives. Believe me, it is alive and well. I know people who have lost jobs because their employers found out about their illness. We are told that we are ax murderers even though we have no history of violence or making threats. Friends decide that they want nothing more to do with us. Spouses panic and file papers for divorce. Now they will say that we harbor these impulses in secret, that we are all ticking time bombs.

Andreas Lubitz kept his illness a secret, I suspect, because of what would have happened to him. He would have lost a lucrative job. He might have found himself unemployed for months or even years. Friends would shun him. He would find himself very alone. In the final analysis, because he could not reveal his ache — because he could not talk about it without bringing an end to the life he had worked so hard to create for himself — the pressure built on him. When he found himself alone at the controls of the jet, he forgot the passengers. Only his pain was real to him and he ended it in the most powerful way he could.