I’m always a little on edge when I sit down to watch a movie about someone living with mental illness, particularly if it is a true story. Did the actors, writers, and director get what it is like to live with mental illness or did they make a caricature of it? Did they romanticize it? Did they put a hockey mask over the face of the sufferer and an ax in his hand? Is it another ECT scene out of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest? Or do we get the truth?

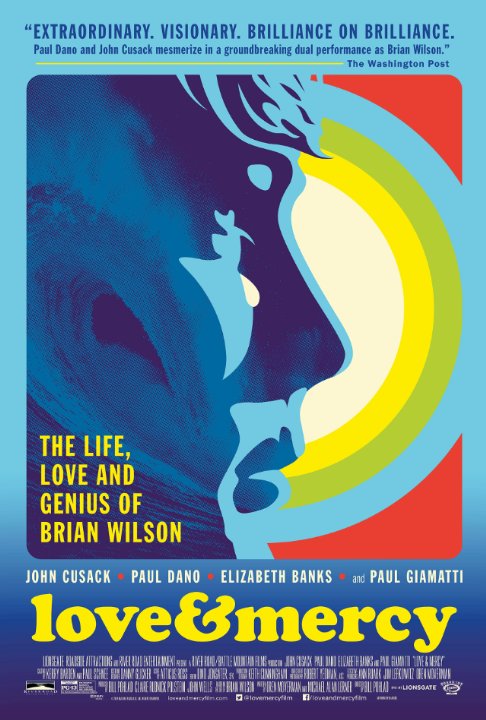

Bill Pohlad’s Love and Mercy had me worried about romanticization before I saw it. I dreaded that he would render the illness of Beach Boy Brian Wilson as cute and fuzzy, something that would make us wonder whether we were too cruel when it came to the mentally ill. It did do that, but there is a right way to go about it and a wrong way. The wrong way declares that there is no such thing as mental illness; it diminishes the impact that the illness has on those closest to the sufferer and suggests that the illness that afflicted the likes of Brian Wilson was little more than a personality quirk. Pohlad and his cast did it the right way: it acknowledges the severity of Wilson’s illness, but also turns a harsh eye towards his guardian/therapist, one Eugene Landy and his sadistic oversight of the musical great. Paul Giamatti’s performance was so to the T that when Wilson watched the movie, he experienced a severe dissociative state where he believed for several minutes that Giamatti was Landers come back to haunt him.

The film does not question whether Wilson suffered from mental illness or whether it destroyed his life. In a unique double-portrayal of Wilson as a manic young man and as a drug-subdued middle-aged one, Paul Dano and John Cusack leave us with no doubts. In a series of intercalated scenes that flip back and forth between Wilson’s youth and his middle age, we are shown Wilson as he begins his decline into madness and as the over-medicated victim of helicopter-caretaking that he became under the supervision of Dr. Landy. Wilson was no doubt a genius, even as his schizoaffective disorder began dismantling his consciousness. Dano captures this disintegration of the self with gentleness and appreciation of the growing severity of Wilson’s condition. We are given glimpses of elements of Wilson’s family life — such as his domineering father and a confrontative cousin who had no appreciation of Wilson’s insights into the kind of sound that the Beach Boys alone could deliver — which contributed to the songwriter’s emotional and cognitive decline, culminating in three years in bed.

The film does not question whether Wilson suffered from mental illness or whether it destroyed his life. In a unique double-portrayal of Wilson as a manic young man and as a drug-subdued middle-aged one, Paul Dano and John Cusack leave us with no doubts. In a series of intercalated scenes that flip back and forth between Wilson’s youth and his middle age, we are shown Wilson as he begins his decline into madness and as the over-medicated victim of helicopter-caretaking that he became under the supervision of Dr. Landy. Wilson was no doubt a genius, even as his schizoaffective disorder began dismantling his consciousness. Dano captures this disintegration of the self with gentleness and appreciation of the growing severity of Wilson’s condition. We are given glimpses of elements of Wilson’s family life — such as his domineering father and a confrontative cousin who had no appreciation of Wilson’s insights into the kind of sound that the Beach Boys alone could deliver — which contributed to the songwriter’s emotional and cognitive decline, culminating in three years in bed.

Cusack depicts an older Wilson who is the thrall of a sociopathic guardian. His Wilson is subdued and barely able to communicate with the woman to whom he is attracted (played by Elizabeth Banks). He is overmedicated and tortured by the wicked Dr. Landy. We see him cower and tremble when Landy goes into one of his grandiose rages. This man is a prisoner of more than his illness.

Dano and Cusack did not interact with one another during the filming so that each could develop his own ideas about Wilson’s state of mind. This formula works: we get a feeling for the great chasm that separated Wilson’s unbridled psychosis from his tormented “recovery”, of the way that the illness and its treatment changed the man so completely that he was almost not recognizable. If one could hand out a Best Actor to a gestalt, Dano and Wilson would be worthy candidates. Let’s hope they and the rest of those responsible for this masterpiece are not forgotten at Oscar time.

Director Pohlad wondered if the true story of Wilson’s life was too outlandish for the screen. He decided to be faithful to history, however. Yes, Landy really was this bad.

Love and Mercy is one of the best films about the complexities of mental illness — its symptoms, the impact of family and health care providers, the importance of loving friends, and the terror and helplessness that patients can feel when constricted by family, therapists, and their own minds. It tells truths about Wilson and about our conceptions about mental illness, about our too thoughtless willingness to turn control of the lives of its sufferers to guardians who do not have the best interests of the patient in mind. It is a tour de force that deserves viewing by anyone interested in these issues. I mark it as a better movie than One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest because it is honest in its portrayal of the convulsive effects of mental illness on the lives of everyone in the family and the desperation that sometimes drives families to terrible solutions on behalf of the patient. You don’t have to be an anti-psychiatrist to feel the rage that the film elicits against the likes of Dr. Landy. Even those of us who are firm defenders of the medical model — which this film ultimately champions despite Landy’s castle of horrors — feel the rage on Wilson’s behalf.

Thank the Universe that he found a kind woman to be his defender when Landy sought to manipulate and silence him.

If you miss it in the theater, watch for it to come out on video.

Five stars.

Follow

Follow