Mining coal is notoriously dangerous, the remnants of those mines disfigure the Earth, and the by-products of coal’s combustion fill the air not simply with soot, smoke, and carbon dioxide but also with toxic heavy metals like mercury and lead, plus corrosive oxides of nitrogen and sulfur, among other pollutants. When I visited coal towns in China’s Shandong and Shanxi provinces, my face, arms, and hands would be rimed in black by the end of each day—even when I hadn’t gone near a mine. People in those towns, like their predecessors in industrial-age Europe and America, have the same black coating on their throats and lungs, of course. When I have traveled at low altitude in small airplanes above America’s active coal-mining regions—West Virginia and Kentucky in the East, Wyoming and its neighbors in the Great Basin region of the West—I’ve seen the huge scars left by “mountain top removal” and open-pit mining for coal, which are usually invisible from the road and harder to identify from six miles up in an airliner. Compared with most other fossil-fuel sources of energy, coal is inherently worse from a carbon-footprint perspective, since its hydrogen atoms come bound with more carbon atoms, meaning that coal starts with a higher carbon-to-hydrogen ratio than oil, natural gas, or other hydrocarbons.

James Fallows, in his The Atlantic article, Dirty Coal, Clean Future, is not oblivious to coal’s faults, and he explains in some depth about coal’s rather large percentage of carbon dioxide emissions. Unfortunately, the scale of the climate change problem is huge:

As one climate scientist put it to me, “To stabilize the CO2 concentration in the atmosphere, the whole world on average would need to get down to the Kenya level”—a 96 percent reduction for the United States. The figures also suggest the diplomatic challenges for American negotiators in recommending that other countries, including those with hundreds of millions in poverty, forgo the energy-intensive path toward wealth that the United States has traveled for so many years.

The reduction needed is even more than 96% when we add in a portion of greenhouse gas emissions from China, where half of electricity is used to manufacture for export. Unfortunately, we will use coal in the future, a lot:

Precisely because coal already plays such a major role in world power supplies, basic math means that it will inescapably do so for a very long time. For instance: through the past decade, the United States has talked about, passed regulations in favor of, and made technological breakthroughs in all fields of renewable energy. Between 1995 and 2008, the amount of electricity coming from solar power rose by two-thirds in the United States, and wind-generated electricity went up more than 15-fold. Yet over those same years, the amount of electricity generated by coal went up much faster, in absolute terms, than electricity generated from any other source. The journalist Robert Bryce has drawn on U.S. government figures to show that between 1995 and 2008, “the absolute increase in total electricity produced by coal was about 5.8 times as great as the increase from wind and 823 times as great as the increase from solar”—and this during the dawn of the green-energy era in America. Power generated by the wind and sun increased significantly in America last year; but power generated by coal increased more than seven times as much… Similar patterns apply even more starkly in China. Other sources of power are growing faster in relative terms, but year by year the most dramatic increase is in China’s use of coal.

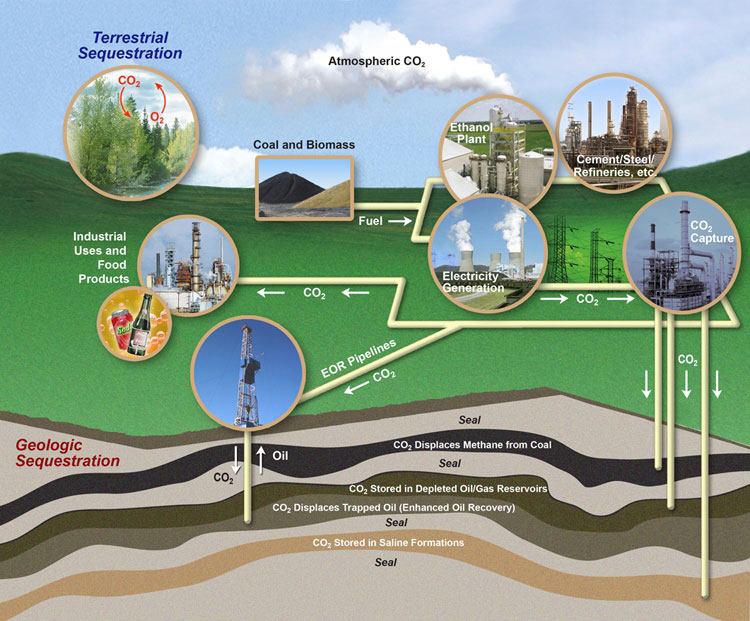

The price of making coal clean, capturing and storing the carbon dioxide, includes a huge energy cost, perhaps 30% increase or more to make the same amount of electricity.

“When people like me look for funding for carbon capture, the financial community asks, ‘Why should we do that now?’” an executive of a major American electric utility told me. “If there were a price on carbon”—a tax on carbon-dioxide emissions—“you could plug in, say, a loss of $30 to $50 per ton, and build a business case.”

Looking at US policy in isolation, there is little reason for optimism, as utilities are refusing to ask ratepayers to pay an extra 3 – 5 cent/kWh for coal. Looking at the US and China together, though…

Ming Sung from the Clean Air Task Force and

Julio Friedmann from Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory

In the normal manufacturing supply chain—Apple creating computers, Walmart outsourcing clothes and toys—the United States provides branding, design, and a major market for products, while China supplies labor, machines, and the ability to turn concepts into products at very high speed.

But there is more cooperation with coal:

In the search for “progress on coal,” like other forms of energy research and development, China is now the Google, the Intel, the General Motors and Ford of their heyday—the place where the doing occurs, and thus the learning by doing as well. “They are doing so much so fast that their learning curve is at an inflection that simply could not be matched in the United States,” David Mohler of Duke Energy told me.

“In America, it takes a decade to get a permit for a plant,” a U.S. government official who works in China said. “Here, they build the whole thing in 21 months. To me, it’s all about accelerating our way to the right technologies, which will be much slower without the Chinese.

“You can think of China as a huge laboratory for deploying technology,” the official added. “The energy demand is going like this”—his hand mimicked an airplane taking off—“and they need to build new capacity all the time. They can go from concept to deployment in half the time we can, sometimes a third. We have some advanced ideas. They have the capability to deploy it very quickly. That is where the partnership works.”

The good aspects of this partnership have unfolded at a quickening pace over the past decade, through a surprisingly subtle and complex web of connections among private, governmental, and academic institutions in both countries. Perhaps I should say unsurprisingly, since the relationships among American and Chinese organizations in the energy field in some ways resemble the manufacturing supply chains that connect factories in China with designers, inventors, and customers in the United States and elsewhere. The difference in this case is how much faster the strategic advantage seems to be shifting to the Chinese side.

Take home point: We need to add a cost to greenhouse gas emissions in the United States and elsewhere in the $30 – 50 range if we are to stop using coal without carbon capture and storage.